Like the liturgists of old, Arlin’s work troubles us where we are too comfortable and comforts us when we are troubled

Jewish public worship centers on communal acts of private intimacy. Intimacy with God. Intimacy with self. Intimacy with our fears and our deepest yearnings. Covering our eyes in Shema. Standing in silence during t’fillah. Receiving an aliyah – going up to the Torah – to say a blessing standing before the Scroll.

The beauty – perhaps even the paradox – is that through these communal acts of intimacy we ultimately achieve an intimacy with one another, with the community and with the Jewish people. When we sing in prayer, it is with one voice, deeply connected. Your yearning becomes my yearning. As individuals, we stand together at the gates of prayer. Ultimately, we pray with both communal acts of private intimacy, as well as communal acts of communal intimacy.

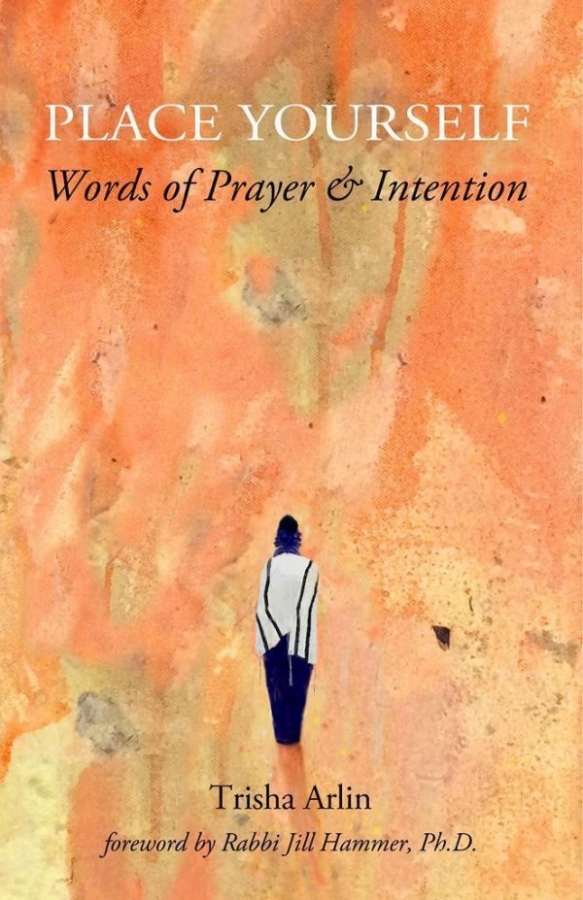

In her new book Place Yourself (Dimus Parrhesia Press, 2019), poet Trisha Arlin addresses the challenge of creating communal intimacy in new liturgy. Her book – available in hard cover (in color) and paperback (in black and white), featuring original artwork by Mike Cockrill – traces Jewish liturgy from key moments in our daily lives to the daily prayers of the siddur. It presents unique offerings for the Jewish festivals, including several poetic commentaries, such as her interpretation of Megillat Esther and a guided meditation for the Amidah.

Arlin’s writing echoes the ancient yearnings of the siddur, laced with poetry arising from individual experiences. She offers moments of great comfort alongside images unanticipated in prayer. The result is both captivating and, at times, unsettling, as Arlin invites us into her rich, personal spiritual life.

Her writing pulls no punches. She artfully weaves private and communal intimacy into her works. The title piece opens the book. “Place Yourself: An Unetaneh Tokef for Rosh Hashanah” is raw and to the point:

“Place yourself in front of the fear.

You will be judged, you will die.

Place yourself in the center of the universe

You earned that spot simply by existing.

Place yourself under obligation to God…”

Part yearning, part theology, part liturgical preparation for the Days of Awe, Arlin draws us into ourselves. Two stanzas later, she draws us together into community:

“…as a congregation, we proclaim:

Let the holiness rise up!

On Rosh Hashanah it is written

On Yom Kippur it is sealed…”

The personal becomes communal. The communal becomes a call to God, resonating with the core language of the machzor.

Arlin weaves her personal experiences and values into many of her works, invoking unexpected imagery. At times that imagery refreshes core Jewish ideas; and at times it can be startling enough to break the spiritual spell of the prayer.

One example: in “Clean Dirt: A Prayer for Tashlich,” she reflects on finding an eco-friendly way to cast sins into the waters. The speaker of the poem picks up “…some twigs and leaves and dirt / and probably some bird poop, too. / I am looking for natural organic green sin…”

Arlin also uses her writing to preach to her readers. In one piece she reflects on the plagues that we recall in the Haggadah as “…not being cute…” In “My Friend, My Captive: A Ritual with Blessings and Confessions for our Pets,” Arlin envisions pets as being in captivity to human beings. In another yet, she creates a vidui – a confessional – for eating animals.

Place Yourself reflects a deep sensitivity. Like the liturgists of old, Arlin’s work troubles us where we are too comfortable and comforts us when we are troubled. At times challenging Jewish theology, at times embracing and elevating it, this book has an important place on the historic bookshelf of Jewish liturgy. It uplifts. It challenges.

Trisha Arlin’s Place Yourself invites us to experience prayer with powerful metaphor, a modern sensitivity and a deep love that at once refreshes the act of prayer and simultaneously invites us back into the siddur to explore the texts of generations past.

Alden Solovy is an acclaimed liturgist of over 700 original works of Jewish liturgy. He recently taught an online course, through the Reconstructionist Learning Networks in collaboration with Ritualwell, entitled “Ingredients of Prayer: Writing Contemporary Liturgy.” His fourth book of new liturgy, This Joyous Soul: A New Voice for Ancient Yearnings, was recently published by CCAR Press.

Trisha Arlin is a regular contributor to Ritualwell, a liturgist and very part-time rabbinic student at the Academy of Jewish religion; 2014 Liturgist-In-Residence at the National Havurah Summer Institute; the editor of RAISING MY VOICE: Selected Sermons and Writings by Rabbi Ellen Lippmann and VOICES, the Kolot Chayeinu Journal; and creator of the Writing Personal Prayer workshops. She blogs at: http://triganza.blogspot.com/.