Is a ritual for saying goodbye to a sacred text appropriate for saying goodbye to people?

Jewish tradition and the Hebrew language have many ways for saying goodbye:

Shalom

Shalom Aleykhem

L’hitraot

I’ve even heard: n’shikot (kisses)/hibukim (hugs)!

We have a very beautiful tradition of saying a specific prayer when finishing, when saying goodbye to, a section of study. This prayer, called Hadran Alakh, in the ancient tongue of Aramaic, speaks to our commitment to return to our text; our goodbye is never final but merely an “I will return to you soon.” Of course Judaism, a religion and culture that has a passionate love affair with its texts, has a meaningful and gorgeous prayer for saying goodbye.

The Hadran Alakh prayer is traditionally used to commemorate completing a study of a tractate of Talmud. This is part of an entire ritual, a siyyum, a completion ceremony. The siyyum celebrates one’s achievement and gives thanks to Hashem for allowing one to engage with the holy text. Traditionally, a siyyum is celebrated after completing a tractate of Talmud but siyyumim can also be used when finishing a book in Torah, reading the complete Nevi’im (Book of Prophets), a chapter of Mishnah, finishing one part of the Shulkhan Arukh or reading the entire book of Tehillim (Psalms). Siyyumim are a way of saying goodbye to a text and a vow to return to it in the near future. Through our study we have become intimate friends with the text, and it is only healthy to have a proper goodbye.

What relevance does this ritual have for us today? Especially for those who rarely will have the time or energy to finish a tractate of Talmud. In today’s society saying goodbye is frequently avoided; people feel uncomfortable with the feelings associated with goodbyes or we become too busy to take the time to properly say goodbye. But what are we missing when we neglect to say a proper goodbye? There is immense healing, closure, and peace in giving our energy to saying goodbye.

But is a ritual for saying goodbye to a sacred text appropriate for saying goodbye to people?

Traditionally, texts within Judaism are considered to be sacred, at times written on parchment by a sofer/soferet in the ancient language of Aramaic or Hebrew, with loving care and attention to detail. But what if we reconstructed our understanding of who and what are sacred texts? What if our texts were not just characters written on a beautiful page but found within us as human beings? In other words, we carry the sacred texts within us: we are the sacred texts.

Rabbi Lawrence Kushner writes: “The words of Torah are holy because they provide a glimpse into the infrastructure of being. They comprise a single ‘living organism animated by a secret life which streams and pulsates below the crust of its literal meaning.’ Midrash tried to imagine ever larger systems of interdependence and meaning. Someday, according to Jewish mystical, or Kabbalistic, tradition, the entire Torah will be read as one long, uninterruptable Name of G-d. And that, of course, would dissolve not only the boundaries between the words of the text, but also the boundaries separating reader from text, creating the ultimate midrash… [Thus] it is not Jacob [in the story about the angels ascending and descending the ladder] who says, ‘G-d was in this place and I, I did not know.’ It is you who are reading these words. You are the sacred text itself. The holy text is not about you. You are not even ‘in’ it. You are it.”

I brought this piece to my Spiritual Autobiography in Contemporary Thought class and my colleague pushed me to look at myself as a sacred text. I retreated back and thought: I’m not a worthy text, I’m not sacred. But this conversation has been sitting with me, and through my work with others, loving and supporting others, I know that each of us is a sacred text and there is extreme beauty and connection through engaging with one another as sacred texts.

How different would our ethics and treatment of one another be if we acknowledged each person as not just b’tzelem Elohim (in the divine image of Hashem) but also a sacred text! Reflect on how we, as Jews, value, cherish, and adore our sacred texts. We kiss them, hold them close, yearn to see them, touch them, eat them like honey. We invoke the holy when we engage with them and when our time with them ends we give them a holy burial, return them to the earth to continue the cycle of regeneration. What care we take with our holy words: imagine the holy care we would give to one another if we viewed each person as a sacred text.

I have a practice of viewing each person and truly listening to what they are saying. Sometimes this listening comes through literal listening to their words; other times this listening is reading their body language or attempting to understand their energy. I then think of the words they are expressing and see the words in Hebrew float past their face, radiate off of them like an aura. This is my attempt to make them a sacred text.

Having the ability to see people as sacred texts is not just a holy practice but also allows us to use the Hadran Alakh to say goodbye to people, not just the literal sacred texts.

הֲדַרַן עַלָךְ מַסֶּכֶת _____ וְהֲדַרַך עֲלָן, דַּעְתָּן עֲלָךְ מַסֶּכֶת _____ וְדַעְתָּךְ עֲלָן. לָא נִתֽנַשֵׁי מִינָךְ מַסֶּכֶת _____ וְלֹא תִּתֽנַשִׁי מִינַן, לָא בְּעָלְמָא הָדֵין וְלֹא בְּעָלְמָא דְאַָתֵי

Hadran alakh Masekhet _____ ve-hadrakh alan da’atan alakh Masekhet _____ ve-da’atekh alan lo nitnashi minekh Masekhet _____ ve-lo titnashi minan lo be-alma ha-din ve-lo be-alma deati

We will return to you, Tractate ____ [fill in the name of the tractate], and you will return to us; our mind is on you, Tractate ____, and your mind is on us; we will not forget you, Tractate ____, and you will not forget us – not in this world and not in the next world. (Hebrew text and translation from Sefaria).

By reciting the Hadran Alakh when we say goodbye to people we stress that goodbye is never forever but merely a “for right now.” It also stresses the act of remembering each other while not in each other’s company. We may not see someone physically for years, but their memory and memories with them remain with us and return to us often. This prayer not only expresses an interest in seeing a text or person again but a request to be reminded of them often.

This prayer also stresses the limitless time frame in which to reconnect; reconnection may not occur in this world but may occur in the world to come (the world that we do not yet know how or where it exists). By using this prayer to say goodbye to one another we bring to speech our belief that people are never forgotten, people are never forever lost but remain with us in thought, loving memory, and perhaps physically in this world or the world to come.

I have revised the traditional Hadran Alakh prayer to say goodbye to sacred people in my life:

I see before me faces of sacred texts. Sacred texts that I cherish and love. Sacred texts that are separate from myself, yet have become part of who I am. I see sacred texts that hold holiness in their words and their beings. Sacred texts that embody our Jewish tradition and our wisdom. Holding closely the memory of seeing the sacred texts within your faces.

הדרן עלייכו כתבי הקודש והדריתו עלן דעתן עלייכו כתבי הקודש ודעתכון עלן לא נתנשי מינכון כתבי הקודש ולא תתנשו מינן לא בעלמא הדין ולא בעלמא דאתי

Hadran alaykhu kitvey hakodesh ve-hadartihu alan da’atan alaykhu kitvey hakodesh ve-da’atkhon alan lo nitnashei minekhon kitvey hakodesh ve-lo titnashu minan lo be-alma ha-din ve-lo be-alma deati

We will return to you, holy, sacred texts before me, and you will return to us; our mind is on you, holy texts, and your mind is on us; we will not forget you, sacred beings, and you will not forget us—not in this world and not in the world to come.

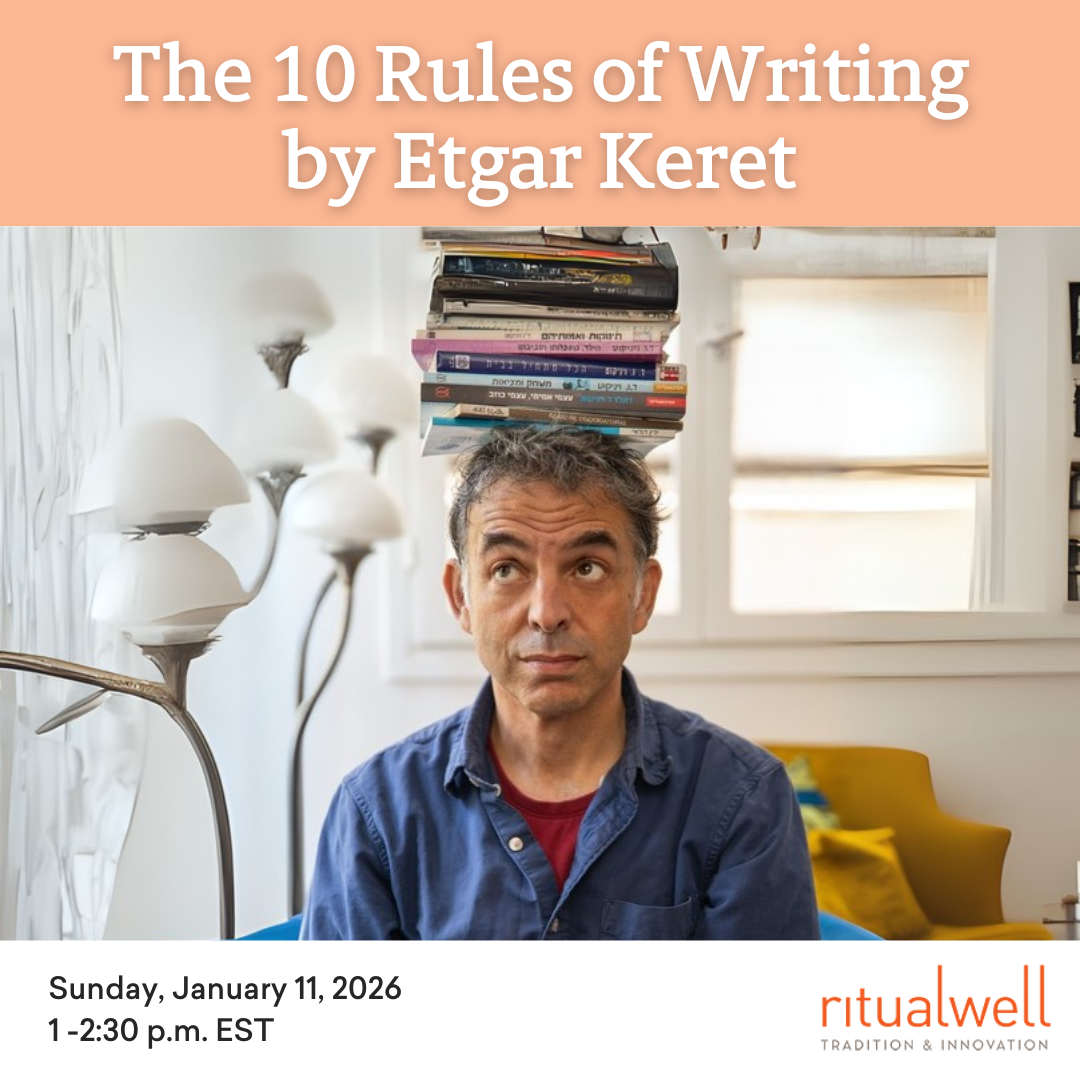

Rabbi Kami Knapp is the rabbinic intern for Ritualwell and was recently ordained as a rabbi by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. The goodbye ritual can be found here.